Cultural Heritage Along the Silk Road

Prof. Francesco Frangialli

Honorary Secretary General of United Nation Tourism (UN Tourism)

The Belt and Road Initiative reminds us that the ancient Silk Roads have been for centuries ways and marketplaces where silk and other products used to be carried and sold. Coming from China, the silk arrived through Italy to my country, France, in the 15th century. King Charles the 7th ordered the two first weaving looms to be created in the ancient city of Lyon.

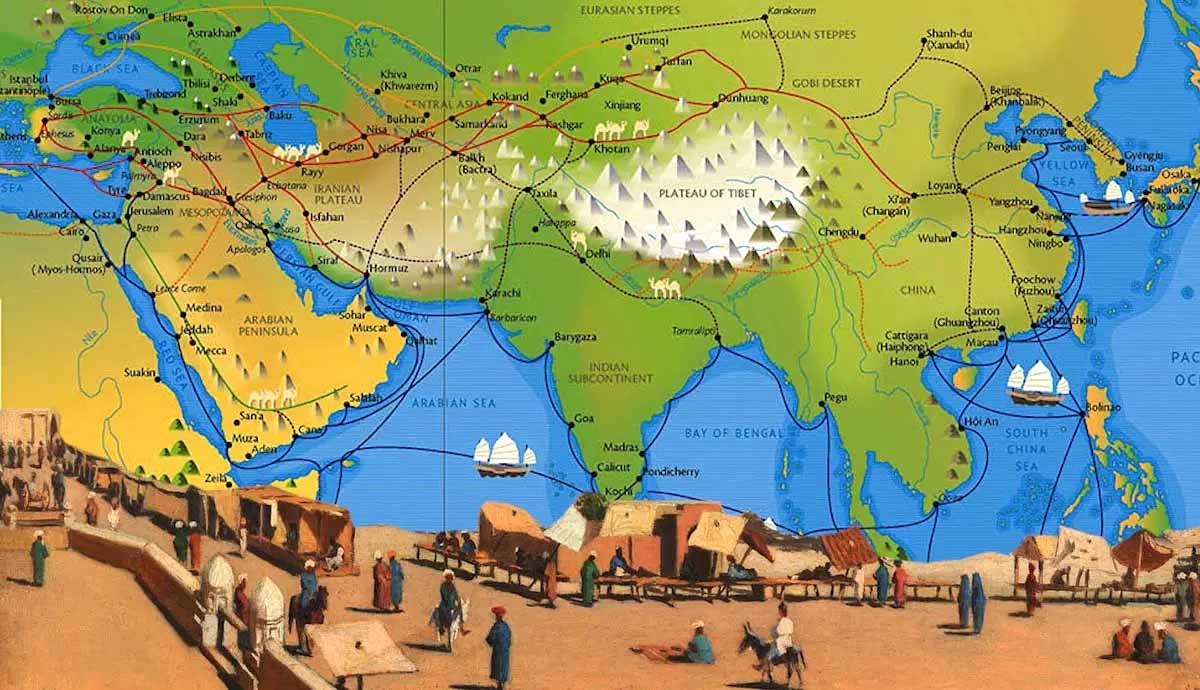

Over 8 500 kilometers, from Japan at the East to Italy at the West, the Silk Roads connected one part of the world to another. They were a link between civilizations which otherwise would have been ignorant of the existence of the others.

The ancient Roads. formed a complex network of paths and highways where goods were transported and exchanged. But their role and importance were going much beyond just trade. Ideas and languages, folk traditions, music and songs, performing arts, festive events, and religious rituals were circulating along these extraordinary Roads.

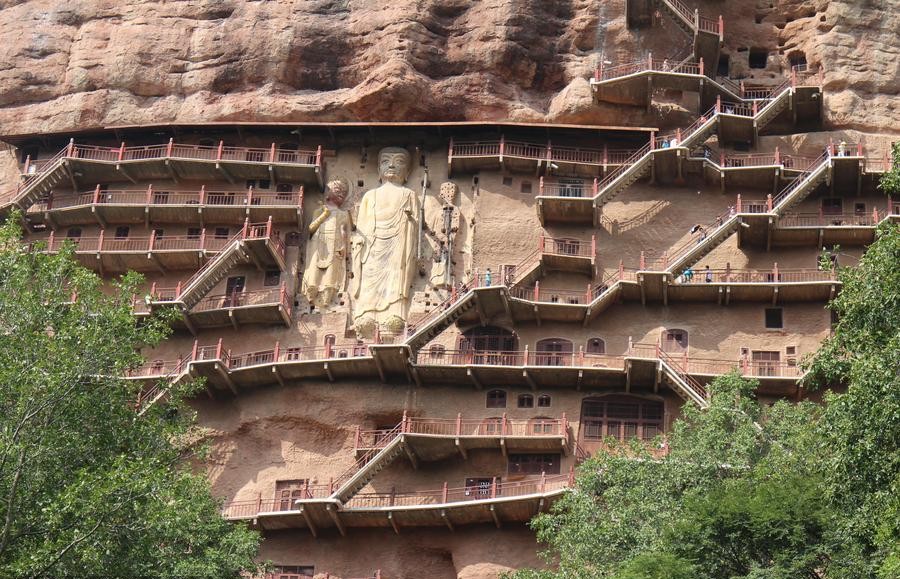

How fascinating is the Greco-Buddhist art, where a statute of Buddha seems to be the one of an ancient Greek kouros! How exceptional is the old mosque of Xian which architecture looks like the one of a Buddhist temple!

Along the Silk Roads, Buddhism came to Ban, Peshawar and Taxila. Islam arrived to Xian. The two religions one after the other settled in Xinjiang. If you make a stop in Xian, at the end of the Silk Road, you will discover the celebrations, religious beliefs, cultural practices, foods, and garments of the Hui people, which have been brought there by the caravans.

Our theme today is the safeguarding and the transmission of the intangible cultural heritage accumulated, carefully kept, and exchanged by the various communities disseminated along the Silk Road, making them the most accomplished example of a shared cultural property over a great distance and a long history.

While fragile, intangible cultural heritage contributes to maintaining cultural diversity in the face of growing globalization. With it we remain faithful to our roots.

The importance of intangible heritage is not only its cultural value itself but the fact that wealth of knowledge and skills is transmitted from one generation to the next.

This kind of heritage is inclusive. It is relevant for minorities as well as for mainstream groups. It is equally important for developing states and for developed ones.

Intangible cultural heritage does not ask the question if certain practices are good or bad. It does not pretend that your culture is better than another. It favors mutual respect and understanding.

It contributes to social cohesion, encouraging a sense of identity and responsibility which helps individuals to feel part of different communities and to the society at large.

Intangible cultural heritage is finally community-based. It is a heritage from the moment it is recognized as such by the groups or individuals that create, maintain, and transmit what belongs to their community, sometimes a small one.

*******

Tourism plays a significant role in the preservation, the adaptation, and the transmission of the intangible cultural heritage.

Traditional pieces of furniture and objects of the daily life of the villagers are more and more replaced in the households by equivalent pieces made in plastic or other vulgar materials. The original ones find a new market since external visitors are interested in purchasing them.

Similarly, festivals, folk dances, traditional art performances, and songs have lost their public as new generations prefer watching screens or spending time on social medias. But tourists have replaced them as spectators; they contribute to the safeguard of this living culture because they appreciate the value it contains. Discovering a different culture is a strong motivation to travel.

A bit more than thirty years after its famous 1972 World Heritage convention the UNESCO adopted in 2003, a second convention devoted to the protection of the intangible heritage. This major international instrument has been ratified by 181 countries.

In accordance with the convention, 788 items have been classified since 2008 in 150 countries. They belong to three categories: the inscriptions on the main list, the intangible heritage in need of urgent protection, and the register of good safeguarding practices, which can be a source of inspiration for others.

Let us illustrate them with examples coming from China, from my own country, France, and from the rest of the world.

*******

Let’s first of all note that a significant part of China intangible heritage comes from the 55 ethnic minorities of your country.

As part of its intangible heritage, you can find examples of music, songs, and other performances: Beijing opera, kunqu extremely old opera, Tibetan opera, Cantonese yueju opera, guqin stringed instrument and its music, nanyin musical performance in the Fujian province, hua’her music in Gansu and Qinghai provinces, Mongolian art of singing, and a kind of theater called shadow puppetry -especially the one in the Fujiang province.

In this category, muqam music in Xinjiang and wind instruments and percussion ensemble in Xian are two examples clearly related to the Silk Road. They belong to the two major Muslim minorities of China: respectively the Uyghurs here in Xinjiang and the Huis in Shaanxi.

Let me make a special mention of the grand song of the Dong people. I keep the memory of a visit to Zhaoxing in the Guizhou province. As usual, the song was performed for visitors and tourists, but in a hidden corner, a group composed of a family and friends was singing for its own enjoyment. Listening to them was a privileged moment.

Dancing is part of the Chinese intangible heritage with among others the Mongolian folk dance and the farmer’s dance of the Korean ethnic group. I made myself ridiculous when I was invited to perform the diabolic bamboo-beating dance during a visit to Shandong. The Party secretary of the province could not stop laughing.

Many Chinese examples of intangible heritage are related to artworks, objects of the daily life, handicrafts, or garment production: Chinese wooden arch-bridge, engrained block printing techniques, seal engraving, wooden movable-type printing, Chinese papercut, calligraphy (with a particular inscription for the one in Mongolia), regong art items in the Qinhai province, sericulture and silk craftmanship, weaving and embroidering, with a special inscription for the Li people, Nanjing yunjing brocade.

Other interesting kinds of the Chinese intangible heritage are related to health and food: tea processing techniques, Chinese traditional medicine, healing such as the bath therapy of the Tibetan people (a hot bath is needed when it’s freezing outside), and acupuncture, which makes me afraid. I hate those needles! UNESCO has forgotten to include in its list the use of chopsticks which make the life of foreign visitors more complicated.

Finally, two main items which correspond to important dates of the year have been included in the list: the spring festival and the practices associated to the celebration of the New Year, on the one end, and on the other the Dragonboat festival, that I shall be attending in a few days’ time in Guangzhou. There are also many local events and celebrations like the Naadam Mongolian festival or the Qiang New Year festival in the Sichuan province.

*******

Ladies and gentlemen, I would like now to present to you four items retained by UNESCO for France, including my hometown, Paris.

The three first ones are about gastronomy since for the French people, just as for the Chinese, food and drink are essential. Gastronomy is important for tourism. For instance, wine tourism -called also oenotourism- which means travelling with the purpose of discovering vineyards and drinking wine, has become extremely popular. Be careful not to have an accident while driving along a wine trail!

As all of you know, France has the best wines in the world (we are not modest when we speak of such an important subject). Two regions are famous for their vineyards: Bordeaux and Burgundy. In the UNESCO list, you will find the so-called “terroirs” of Burgundy -delimited parcels on the slopes of Côte de Nuits and Côte de Beaune, south of the city of Dijon, with their specific landscapes and their rich properties (les chateaux).

Here the problematics of the built and of the intangible heritages enshrined in the two distinct UNESCO conventions are converging. These places blessed by God associate a favorable climate, geologically appropriate conditions, and ancient traditions of cultivation. Wines were imported to the region by the Romans after its conquest by Caesar in 52 BC. “God created the water, man created the wine”, said the French poet, Victor Hugo.

The price of a bottle of the famous Romanée Conti dating from 1947 is around six thousand euros. 1947 is the best year in history for French wines; incidentally, it is the year when I was born.

I would like to underline that what has been achieved in Burgundy could be a source of inspiration for China, and especially for the Xinjiang province, which is located on the heart of the Silk Road. Since 1937, we have in Burgundy a touristic road called “Route des grands crus de Bourgogne” – the vintage wines- which over 6O kilometers links the most prestigious vine estates, that you can find in the area of the UNESCO list I just described before.

The four sites of the Xinjiang province, particularly the one near Turpan, represent one quarter the national output and their potential for growth is important.

Most of the grape varieties used for fabricating the Chinese wines come from France, in particular the Chardonnay for the white wines and the Cabernet Sauvignon and the Merlot for the red ones. I would like to make a suggestion to our friends of the NICE team: to select the theme of wine production -and of course of wine drinking- for the next meeting of our Silk Road Dialogue. Drinking together a good bottle makes exchanges easier.

Be careful however if you decide to follow the French model. Chinese and French food habits are not the same. We drink wine to accompany our meal, just because we like it. For Chinese people it’s a different story: wine is there to celebrate and to express the friendship. Ladies and gentlemen, Kanpei!

French gastronomic culture is about bringing people together thanks to good food paired with fine wines. This is why the UNESCO list includes the French traditional gastronomic meal customarily served during social celebrations like weddings, birthdays, anniversaries, and reunions.

The meal is composed of successive dishes, usually six or seven, accompanied by different kinds of white and red wines. To whet your appetite, the menu starts with a drink, usually champaign. Then come the dishes of different kinds, served before or after the main course which is composed of meat or fish (if you are brave, you may have fish plus meat!). In the mid of such a heavy meal, you will need the so-called “trou normand”: a sorbet plus a glass of a strong alcohol such as Cognac, Armagnac, or Calvados -the last one coming from Normandy, gives its name to the practice. After the “trou normand”, your stomach has been cleaned up and you can start eating again!

*******

A piece of food classified recently by UNESCO is the French stick, that we call “baguette”. It is not any kind of bread. Made of white wheat, it is 65 centimeters long and its weight is about 250 grammes. You can eat it just like that or use it to push discretely your food to the fork. French people love that kind of bread, they purchase it every day at the bakery and very often carry it under their arm on the way back home. Six billion baguettes are sold every year.

A baguette accompanied by a good cheese (we have 1,200 different kinds of cheese in our country), and a glass of red wine is enough to make a French person happy.

I come to my last point concerning France. I was in China on the 15th of April 2019 when in the mid of the night I saw on my telephone that Notre-Dame cathedral in Paris was burning. My Chinese friends were as desperate as myself since it was a precious piece of the world heritage which was close to disappear. Notre-Dame dates from the 12th century; it belongs to the Parisians, to the French, to the Catholics and to everybody in the world.

The fire was stopped at the last minute, just before the fall of the two main towers which would have made the damage irreversible. We reconstructed our beloved church in five years. Its doors were reopened on the 8th of December, and the Christmas mass could be celebrated before the end of 2024.

How was the performance of a reconstruction within the short delay of five years achieved? For a simple reason: because the intangible heritage came to the rescue of the built heritage.

The figures are impressive. 1,300 cubic meters of stones were needed, coming from nine different sites of the Paris region. For the wooden frame, called the “forest”, almost fully destroyed, one thousand oaks with a minimum length of twenty meters were cut down all over France or even imported from abroad. To restore the great organ damaged by the smoke, 8,000 tubes had to be disassembled, carefully cleaned up and reinstalled. The refurbishment had to be complete since all the existing furniture had been reduced to ashes. The roof was faithfully reconstructed with a lead cover.

The result was magic: the sound produced by the organ is even more harmonious than it used to be. The new wooden frame is identic to the original one dating from the Middle Ages, that I was able to admire in my childhood.

How was all this made possible? By the appeal to the intangible heritage. Five teams with a total of 175 scientists from several universities and research centers guided the process. Two thousand workers, most of them highly qualified, from 250 enterprises were employed: engineers, carpenters, scaffolding workmen, stonemasons, sculptors, glassmakers, painters… Almost everything was handmade; modern technologies were used to give strength to traditional skills.

Many of the craftsmen belonged to very ancient brotherhoods, whom for many of them had kept alive a knowledge dating from the Middle Ages. A friend of mine runs a building company that participated in the restoration of the roof of the building, a company created by his ancestor under the reign of Napoleon and which, from generation to generation, has always remained within the same family.

The skills of Parisian zinc roofers and ornamentalists have been added to the UNESCO list in 2024. Since the mid of the 19th century, the technique gives their unity and harmony to Parisian roofs.

As far as I know, the restoration of Notre-Dame cathedral is the most striking example in history of the strength and the permanence of the intangible cultural heritage.

*******

China, France, but also, last but not least, the rest of the world, for which I have to be selective. I cannot mention each of the 788 items.

The intangible heritage related to music, songs and theater is impressive: Byzantine chant in Greece and Cyprus, opera singing in Italy, Irish harping, Raï folk song in Algeria, fado in Portugal, sodade in Cabo Verde, reggae in Jamaica, guarania in Paraguay, mariachi in Mexico, Buddhist chanting in Ladakh, Jammu and Kashmir, Arirang folk song in Korea, rituals of the Japanese imperial palace, vedic chanting in India.

In the same category, there are also traditional bagpipe in North Macedonia and Turkey, frenetic sega tambour and romantic maloya rhythms in three of the Indian Ocean islands, traditional dance in Oman, music of the Bakhshis in the Khorasan province of Iran, song of Sanaaa in Yemen (let’s hope it will survive to the war), orchestra music of the Chopi community in Mozambique, polyphonic singing in Georgia and the one of the Central African Pigmies (we are too tall for joining them), sanskrit theater in the Indian province of Kerala, nogaku theater in Japan.

Concerning Japan, let me say a word about the renown kabuki theater. During the UNWTO 2001 General Assembly in Osaka we attended a kabuki performance. I confess that I was falling asleep when prince Nahurito, the future emperor who was sitting close to me, asked politely: “do you like kabuki?” A bit confused, I answered that it was something very complicated to understand in my western culture. Then I resumed my sleeping.

Music accompanies dancing. In the list we can also find Congolese and Cuban rumba (they are different), dancing In Bali (the girls are beautiful, just as the ones performing the royal ballet of Cambodia), saman dance in the Aceh province of Sumatra (just for male dancers, as it’s a very strict Muslim region), tango in Argentina and Uruguay (it’s really sensual, but not as much as belly dancing in Arab countries), whirling dances in Turkey, flamenco in Spain, calypso in Trinidad and Tobago which expanded to the Caribbean and Venezuela, carnival of Barranquilla in Colombia, music and song in southern Viet Nam, ethnic mangwengwe dance in Zambia, sophisticated cheoyoungmu dancing in Korea, gagaku ancient dancing in Japan, traditional Albanian, Polish and Hungarian dances, waltz in Vienna and elsewhere.Other inscriptions are about food and beverage: bortsch soup in Ukraine and Russia (they are at war to know which one is the best), skill of the Napolitan pizzaiolo in Italy, Turkish coffee (not to be confused with the Greek one or the Arabic one, each side would not appreciate), harissa sauce to make a good couscous in Tunisia, wine-making technique in Georgia, multi-ethnic breakfast culture in Malaysian beer culture in Belgium (blonde or dark, you can choose), cider culture in the province of Asturias in Spain, Vevey winegrowers festival in Switzerland, mashed potatoes dish in Estonia, special diet in seven Mediterranean countries -just to get slimmer…

Outdoors sports, leisure activities and health make a third group: hurling in Ireland, camel racing in Emirates and Oman (the animals can be a bit lunatic), Karabakh horse-riding game in Azerbaijan, cruel and violent bozkachi horse game practiced from Afghanistan to Turkmenistan along the Silk Road, nomad migration and associated practices in Mongolia, wrestling in Georgia, Bangladesh rickshaws (they go too fast like the ones in Thailand), Spanish riding school in Vienna and lipizan horse breeding in various European countries, equestrian art in Portugal, sauna culture in Finland and Estonia (sometimes it is too hot), traditional Thai massage (the really medical one, not the other kind), yoga in India, Bedouin cultural practices in Jordan, cultural activities performed on Jema el-Fnaa square in Marrakech, Morocco.

A last group comprises handicrafts and fabrication of other usual objects: traditional violin craftmanship in Cremona, Italy, watches making in Switzerland (they give you the exact time, no excuse for being late), Indonesian batik, carpet weaving in Kyrgyzstan, Iran and Azerbaijan, Indonesian kris (be careful, it is a dangerous weapon), wood crafting knowledge in Madagascar, Syrian traditional glassblowing and Aleppo Ghar soap in the same country, soap making as well in Palestine (caution, it’s slippery!), ceramic arts in Uzbekistan.

*******

The examples I have listed demonstrate that intangible cultural heritage is traditional and living at the same time. It does not only represent inherited traditions, but also contemporary practices in which diverse cultural groups take part.

I am convinced that in the small village of the Alps and in Paris, the two places between which I share my life, as well as here in Chengdu and the other parts of China and the world where you come from, we can find many examples of the intangible cultural heritage. It governs our lives and the ones of our communities. It offers us the guarantee that what we have received as a gift and what we have enjoyed as a happiness will continue to exist.

Copyright Institute Tourism

Prof. Francesco Frangialli

Honorary Secretary General of the United Nation Tourism (UN Tourism) and the former Director General Tourism of France.