The seven major challenges facing tourism today

Conflicts, climate change, biodiversity & ecotourism, overtourism, sustainability, recognition by the international community.

The purpose of this text is to address the seven major challenges that from my point of view world tourism is facing today, starting with the sad international news of the moment.

Two simultaneous wars are raging, which, although being geographically distant, influence each other. And this, not counting the various international or domestic sources of tensions. For the first time since 1945, war has returned to Europe, impacting global tourism significantly as Europe remains the leading continent for both domestic and international tourism exchanges.

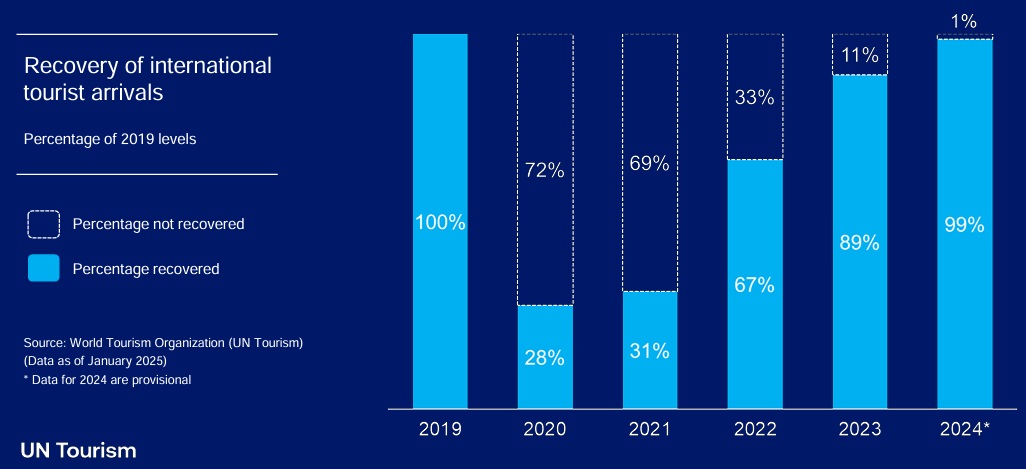

Yet, global tourism is thriving. The World Tourism Organization (UN Tourism) estimates that in 2024 international tourism arrivals have reached 1,445 billion, 99 per cent of the 2019 level before the Covid crisis. It represents an increase of 140 million over 2023. The growth in financial flows -revenues and expenditures- is even more marked than the movements of people.

According to IATA, with 4,9 billion passengers, global air transport has overpassed by 3,8 per cent in 2024 the 2019 peak level. The occupancy rate of the seats has reached 83,5 per cent. A surge of the traffic of 8 per cent is expected in 2025.The pandemic claimed 17 million lives, but tourism is still alive!

A region of the world is particularly suffering from war: the Middle East, since the horrific events of October 7, 2023, and the tragedy which followed.

However, the region’s tourism, which General de Gaulle once called “the complicated Orient,” is also doing well: In 2024, arrivals to the region have reached 95 million, exceeding those of 2019 by 32 per cent. Surprisingly, Middle East is the part of the world where tourism rebounded the quickest after the end of the pandemic.

What is this due to? Mainly to the fact that the major destinations are not directly impacted.

Israel, the Palestinian territories, neighboring Jordan, and Lebanon are at the eye of the storm; tourism activity is naturally halted, adding to the suffering of their populations. Yemen and Syria remain embroiled in their never-ending internal conflicts.

But the great destinations belong to another world. Egypt, once a frequent victim of terrorism, now operates on a logic not of peace or war, but on one resulting from its exceptional cultural heritage. Fueled by significant archaeological discoveries, the country welcomed 18 million visitors in 2023. Pilgrimages continue unabated to Saudi Arabia, which, like Egypt but for a different reason, benefits from a captive market.

Economic activity remains high in the Gulf, where oil exports are hardly affected by ongoing conflicts; far from the epicenter of the earthquake, Dubai continues to magnetize visitors and remains a favored destination. The UAE recorded 28 million international arrivals in 2023. Qatar is booming.

Contrary to what might have been feared the Arab-Muslim world as a whole is only marginally affected by the desolate image given by the Holy Land, where, despite rare moments of ceasefire, fighting rages. Some of its successful destinations, like Turkey and Morocco (with respectively 55 and 15 million international arrivals in 2023), and the Mediterranean in general, may even benefit from a delayed effect.

We can cautiously draw an initial conclusion from this situation: tourism may overreact to an external shock, such as a terrorist act, especially if it is heavily publicized. However, except for a region directly victim of an open conflict, tourism proves to be relatively immune to international tensions unless it is directly involved.

I shall stop here with this first challenge. It shows that in the period we are living, the factors explaining the growth of global tourism, as well as the reasons behind its disruptions, are not unidimensional; they cannot be found exclusively in war and peace between nations, as Tolstoy and Raymond Aron each described in their own ways.

We have come to a first conclusion: the holistic geopolitical explanation that might help us understand what is happening before our eyes lies elsewhere than in international tensions. Our thread for understanding is starting to unravel. Let’s follow it to the next step.

First, let’s look at the COVID epidemic from 2020 to 2022, the most violent shock in the history of international tourism, even more brutal than the 2008 subprime crisis.

Between 2019 and 2020, international tourist arrivals plunged by around 72%, with both developed and emerging countries seeing declines of the same magnitude. Foreign exchange earnings for countries collapsed by similar proportions. 2021 was a year of stagnation, and it wasn’t until 2022 that tourism and air transport businesses began to recover significantly.

This unprecedented COVID crisis calls for five key remarks.

Firstly, while the epidemic halted tourism activity, it did not annihilate it. Activity resumed after two years. The desire to travel did not disappear; on the contrary, since it was frustrated, it became more intense. The financial savings accumulated during this period were dedicated to travel and relaxation and have been used as soon as people could.

History, since the advent of tourism statistics, shows that after every major crisis, international tourism experienced a rebound, as sharp as the dip that preceded it. Every time, it returned to its growth trajectory, which has, and will again, be its long-term trend. This is happening one more time.

Secondly, whether transmitted by the flesh of a poor pangolin, the bite of a stray bat, or a leak from a hidden lab in Wuhan, COVID is a gift from China. Like SARS, tourism was both a vector and a victim of the disease. This is typical of a globalized society, where phenomena such as epidemics, climate change, major pollutions, migrations, terrorism, ignore borders. How can we prevent a highly pathogenic virus from leaving its epicenter and spreading when more than a quarter of humanity moves from one country to another every year?

Thirdly, COVID was the first real pandemic in history to have a significant impact on global tourism. The so-called Spanish flu of 1918, with its tens of millions of deaths, preceded the era of the “leisure society” dear to Edgar Morin and Joffre Dumazedier, and mass tourism. The Asian flu of 1958 and the Hong Kong flu of 1968 were less severe than the initial episode. The first one to be clearly international and to affect an democratized tourism industry was the SARS in 2002-2003, but the phenomenon remained essentially confined to Asia.

The almost biblical catastrophe of COVID was therefore exceptional. We lived through what Jean de La Fontaine describes in Les animaux malades de la peste (The Sick Animals of the Plague): “They did not all die, but they were all struck.” However, no epidemiologist will dare claim that, whether through an H5N1 avian flu mutation that would have become human-to-human transmissible, the resurgence of one of the sinister Ebola or Marburg hemorrhagic fevers, the spread of the new monkeypox, or some other nasty surprise coming from a forest in Congo or a farm in Guangdong, it won’t happen again. And perhaps even more terrifyingly.

Let’s make an essential observation: for tourism a health crisis has many points in common with an economic depression, such as the subprime crisis. When activity stops, when households’ income dries up, when unemployment rises, people become cautious and limit their travel. But with a pandemic, it’s worse—the scale is different since the direct economic impact is present in the same way, but it is compounded by the lockdown and other drastic and blind constraints imposed by governments to prevent the spread of the infection.

How can you travel when planes are grounded, roads are blocked, and enormous cruise ships threaten to become floating coffins? How can you live comfortably and relax when hotels, bars, clubs, restaurants, ski lifts, marinas, amusement parks, and most shops are closed?

From that consideration comes a final observation: in the face of the epidemic, the different segments of the tourism industry have not all been affected in the same way. Some suffered more than others: air transport, cruises, skiing and winter sports, business tourism, fairs and exhibitions. Conferences were replaced by online discussions, on Zoom or elsewhere.

Other sectors, on the contrary, withstood and, to some extent, benefited from the crisis: rural tourism, mid-altitude mountain tourism, ecotourism, outdoor sports, and local leisure activities. Many believed that choosing these sectors was a way to stay protected—both people trying to avoid contamination and, symmetrically, tourism industry players selecting activities less vulnerable to external shocks.

In response to the epidemic, domestic tourism was often, and logically, preferred over international tourism. It is, to some extent, likely to remain so, driven by the growing conviction that we must save energy and reduce emissions, and by the sharp rise in the cost of air travel which penalizes long-distance destinations.

*******

Tourism industry stakeholders face a critical question: is the shift in behavior temporary, or are we witnessing a long-term change in how people balance leisure and work? For the so-called digital nomads, remote work has become a reality, even while traveling. We are facing a reversal of values, fundamentally altering our relationship to both tourism and leisure. Temporary or lasting? Probably a bit of both, depending on the destinations and the products involved.

*******

Thus, by analyzing the crisis we’ve lived through, we are approaching the sought-after explanation. Our thread continues to unravel. Let’s follow it to the next step.

In the face of a major crisis like this, it’s clear that tourism is best protected when it is diversified in its products and markets, when it respects the environment where it operates, when it knows how to conserve a more expensive energy. In summary, when it’s flexible in adapting to circumstances, but always gentle, measured, and responsible in the forms it takes. In short, when it is sustainable.

The Chinese have a word—weiji—to describe a crisis. It’s made up of two characters: one meaning disaster, the other one meaning opportunity. The COVID crisis was a disaster for global tourism; but it offers an opportunity to rebuild it better. As António Guterres, the UN Secretary-General, said in 2020: “It is imperative that we rebuild tourism in a safe, fair, and climate-respectful way.”

Let’s focus on what, in my view, constitutes the heart of the sustainability issue for the tourism industry—the factor that outweighs all others: the warming of our Planet. Let’s extend our thread in this direction.

Tourism, including air transport, is both affected by and contributes to climate change which represents four to five percent of the greenhouse gas emissions.

Last November, in Baku, the COP29 (Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change) took stock of a planet where both air and ocean temperatures are rising in an increasingly uncontrollable manner. The results of the meeting were not impressive: developing countries failed to obtain the substantial financial commitments they demanded from the wealthier nations.

And what a curious idea, by the way, to meet in Baku after gathering the previous year in Dubai: it seems the more a country contributes to greenhouse gas emissions, the more it should be rewarded! But didn’t the President of Azerbaijan say that “oil and gas are a gift from God?”

His government, like others, intends to increase its production of hydrocarbons. In the same vein of inspiration, the newly elected President of the United States aims to “protect the American car industry from the green scam”; he wants to revive drilling and massively deploy hydraulic fracturing. India continues to aggressively build coal-fired power plants, which already account for a third of its CO2 emissions. Let’s not remind Saudi Arabia and others that one year before, COP28 in Dubai called for “a fair, orderly, and equitable transition away from fossil fuels” …

According to the European Copernicus Observatory, the global surface temperature in 2024 exceeded the pre-industrial average of 1850-1900 by 1.6 degrees Celsius. The phenomenon is accelerating, as demonstrated by the sixth International Panel on climate Change (IPCC) report. No one believes in the Paris Agreement’s goal anymore: keeping the warming below 2 degrees, and preferably at 1.5. The UN’s new forecast is 3.1 degrees. The temperature of the oceans is half a degree higher than the 1991-2020 average.

*******

Climate change affects all sectors of the tourism industry, but not in the same proportions or ways.

Tourism in coastal areas is a victim of rising sea levels, which result from the melting of the Greenland and Arctic ice sheets, while even Antarctica is starting to feel the effects of unusual temperatures. Neither Britannia nor anyone else “rule the waves” any longer: an iconic destination like Venice regularly sees St. Mark’s Square submerged by the waters of its lagoon. The Serenissima is becoming less and less so.

At the opposite end of the globe, another major tourist attraction is also suffering: the Great Barrier Reef off the coast of Australia. Home to the world’s largest ecosystem, it has already seen 80% of its coral affected by bleaching caused by rising temperatures and acidification of waters. When coral reefs bleach before dying, an entire extraordinary marine fauna disappears. The magic of diving fades; a world without colors is not a world we are keen to discover.

Rising sea levels and warming oceans are also increasing the intensity of hurricanes and storms. The El Niño phenomenon is intensifying. From the Caribbean to the Indian Ocean and the Eastern Pacific, cyclones indiscriminately sweep away homes, hotels, and beaches, as we’ve recently seen in Florida, the Philippines, Mayotte, and Valencia in Spain. Such extreme events can be disastrous for the tourism industry: New Orleans, which economy depends on leisure and conferences, is just now recovering from the effects of Hurricane Katrina in 2005, the most violent hurricane ever to hit the USA.

The world of science fiction imagined in Isaac Asimov’s Naked Sun is here: extreme temperatures, dried-up vegetation, violent winds, and uncontrolled wildfires periodically sweep across Greece, Canada, Australia, and Siberia. Los Angeles burned in January, and the 2028 Olympic Games will suffer as a result. Even the Amazon rainforest is being devoured on all sides by tens of thousands of fires, ceasing to be the planet’s primary carbon sink. It lost an area equivalent to the one of Italy in 2024. Indonesian rainforests are shrinking even faster.

But the worst may be for the small coral islands in the Pacific and Indian Oceans, where tourism is the main economic resource. Their populations live at sea level; their very existence is at risk. One can understand the injustice felt by the inhabitants, given that these poor communities contribute nothing to emissions.

For example, 80 per cent of the Maldives territory is situated less than one meter above sea level so that a rise of 20 to 30 centimeters would have destructive effects. Erosion is already accelerating, taking away the sand from the beaches. The IPCC predicts that the islands will be gone by 2100. What a waste when the Maldives have reached two million visitors in 2024! Thanks to tourism, the archipelago has managed to escape from the list of the 45 least developed countries.

Particular attention must be paid to the changing climate in mountain tourist areas.

As both the IPCC and UNESCO have pointed out, climate change is more pronounced in mountains and polar regions than anywhere else. In the Pyrenees, the average temperature has risen by 1.7 degree since 1880—exactly twice the global increase. By 2040, the glaciers there will have disappeared. In Chamonix, in the Alps, the Mer de Glace of my childhood, the one from La Grande Crevasse by Roger Frison-Roche, is now just a remnant of the splendor it had. People used to come from afar to admire it, and, descending from the Aiguille du Midi via a staircase of ice, many in winter had the joy of skiing there.

Warming means less frost and snow in winter, and less predictable weather. Mort Shuman could still enjoy us when we play his famous hit: “It’s snowing on Lake Maggiore.” But whether we recall the harsh snowy winters of the past or whether we recall the beauty of the women who have crossed our life, don’t we embellish the nostalgic and fleeting memory we keep of them?

“Where are they, Sovereign Virgin?

But where are the snows of yesteryear?”

Sang the poet François Villon so long ago.

Warming means landslides, falling rocks, and icefalls that await climbers and hikers; it means the exhaustion of water resources, the sudden draining of glacial lakes, and landslides threatening villages downstream. Warming leads to the moving of the upper limit of the forest, the transformation of the landscapes, and the retreat of a very specific biodiversity.

The powerful winter sports industry is, of course, the first to feel the impact of rising temperatures. It is suffering from the retreat of the snow cover, its increasingly uncertain presence at medium altitudes, and the shortening of the ski season. However, all hope is not lost: no doubt of course that the desertic dunes of Saudi Arabia will be covered by snow in 2029 when the country hosts the Asian Winter Games!

But alpine skiing and its 150 million practitioners are not alone in keeping up with the warming: to varying degrees, all forms of mountain tourism are feeling the impact of climate change. From the Alps to the Caucasus, from the Andes to the Rockies and the Himalayas, the mountains are getting too warm, and the concerns of mountaineers are the same.

The mountains are not to become necessarily less attractive; their landscapes will still be magnificent. People will still admire the silhouette of the Atlas Mountains from the palm groves of Marrakech, but some winters, the snow will no longer covers its peaks. By 2050, Mount Kilimanjaro will have changed its face when the glaciers have disappeared from its summit. The mountains will remain just as welcoming, but they will look different.

Moreover, climate change is not the only factor affecting the lives of mountain communities that depend on tourism. Other factors are at play. The clientele is changing, visitor behavior is evolving, and the quest for health and well-being associated with altitude is increasingly shared. Visitor numbers are rising—sometimes excessively.

From our beloved Mont-Blanc to the imposing Everest, from the stunning Table Mountain in Cape Town to Fuji-Yama and the misty peaks of Mount Huangshan, overtourism has become the enemy of the most prestigious summits of our mountains. Everywhere, overtourism, in its various forms, has become the opposite of sustainability.

However, the excessive visitation of remarkable places is by no means limited to the mountains. Let’s look at the islands and archipelagos where space is limited. Porquerolles, Skye, Mykonos, Ibiza, Lanzarote, the Lofoten Islands, Easter Island, the Galapagos, Hawaii—all are on the brink of asphyxiation. Phuket as well, which welcomed 13 million tourists in 2024, a third of Thailand’s total. Will Santorini face a disaster coming from the presence of 3 million visitors or one from a volcanic eruption such as the Aegean Sea collapse in 1610 BC? The excessive number of visitors is affecting major natural sites, such as, in the United States, the Grand Canyon, Niagara Falls, Mount Rushmore, Yellowstone National Park, and the Smoky Mountains.

Overtourism exerts unbearable pressure on iconic monuments and museums, such as, in Italy, the Leaning Tower of Pisa, the Ponte Vecchio and the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, Pompeii, the Vatican Museums and the Spanish Steps in Rome, Saint Mark’s Square in Venice, and the famous “Lover’s Lane” of the Cinque Terre. Elsewhere in the world, spectacular cultural sites such as the Forbidden City, Machu Picchu, Borobudur, Angkor, Petra, Abu Simbel, the Parthenon, the Blue Mosque, and Hagia Sophia are mere shadows of what they used to be.

Look at Egypt! The magnificent Saint Catherine’s Monastery in Sinai, just out of the Middle Ages, suffers from unbearable pressure, boosted by the proximity of the powerful tourist hub of Sharm El Sheikh. But there is still some good news. The Grand Egyptian Museum, located in Giza, has come to the rescue of the chaotic old Cairo Museum, which was overwhelmed by the number of visitors and unable to display some of its most beautiful treasures!

And not referring here to the peak frequentation of these places. Try accessing the Sambadrome in Rio on a Carnival night, Moscow Red Square on May Day, the Great barely Wall of China during Chunyun (Spring Festival week), or Mont Saint-Michel on a busy May weekend!

Overcrowding causes congestion in the streets of cultural cities, especially but not exclusively European: Venice, already mentioned, Bruges, Berlin, Barcelona, Lisbon, Prague, Krakow, Lucerne, Dubrovnik… The list is not exhaustive. For certain cities, the pressure is at a maximum. How can the 55,000 residents of Venice’s historic center continue to host 22 million visitors? Or the 1.7 million inhabitants of Barcelona receive 12 million visitors? Or the 1.5 million of Kyoto see 50 million passing through?

The quality of services provided to visitors suffers. Residents of neighborhoods previously ignored by tourists complain about the noise from late-night arrivals in their rental apartments. They suffer from the invasive presence of others drinking (often drinking too much and noisily, that’s the point!) at the base of their building. At the entrances to museums and monuments, lines stretch longer.

In the narrow streets of historic neighborhoods, pedestrian movement becomes difficult. Popular with tourists, rental bikes are left abandoned on sidewalks. Coaches transporting elderly and mobility-impaired tourists cannot access main attractions or park there. In restaurants, table service is under pressure from impatient clients, which deteriorates the experience, as it does for the kitchen work, albeit less visibly.

Innocent victims of mass tourism, the lovely ladies of Amsterdam’s Red-Light District, as well as their distant cousins, the experienced geishas and novice maikos of Kyoto’s Gion district, no longer know how to (I’m searching for the word…) let’s say, pay with their bodies and deliver the high-end services that have made them famous, without altering their charm.

“Tourists go home!” one reads on the walls of some cities: this scourge of modern tourism has, in turn, provoked a reaction from exasperated locals. Often, the protesters are the same people who once lived off tourism and encouraged its growth. Others, who rent their apartments when they go on vacation, complain that there are too many people when they return. As Jean Mistler wittily writes: “Tourism is the industry that involves transporting people who would be better off at home to places that would be better off without them.”

Excesses lead to measures that limit or even ban rentals like those on Airbnb, as seen in Amsterdam, Athens, Barcelona, Berlin, Lisbon, Madrid, Paris, and in many other cities. In 2024, Spain recorded a record 98 million international arrivals, and its government has taken at the national level severe tax measures to limit the purchase and rental of tourist accommodations by foreign residents.

Quota systems or advance reservations are also being implemented, along with tolls for city-center access, such as in London, Paris, Rome, Milan, Venice, and even New York, or for entering monuments. The sublime Anita Ekberg could no longer display her generous charms to Marcello Mastroianni to entice him into the Dolce Vita in the Trevi Fountain, as access is now controlled and may eventually require payment.

Will it soon be necessary to subscribe to a required quest to enter the Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris, which reopened its divine doors in December, as is already the case for Barcelona’s Sagrada Familia, Milan’s Duomo, the Mosque-Cathedral of Cordoba, and the Great Mosque of Casablanca?

This phenomenon of rejection also applies to the enormous cruise ships that pollute more than they enrich. The city of Nice has recently banned stops for those carrying more than 900 passengers as the one of Venice has done since 2021 for those of more than 25 000 tons.

*******

The World Tourism Organization defines overtourism by the irritation it causes among host communities, but also among visitors themselves, who perceive it as a nuisance. The criterion is interesting but insufficient, as this issue equally affects natural or cultural sites that are inhabited. For these, overtourism can be defined by the excessive number of visits -especially at certain times of the year- relative to the site’s carrying capacity (if this can be established).

Some speak of tourismophobia and view overtourism as the elitist reaction of those who used to travel peacefully before being joined by the masses. This explanation seems somewhat short-sighted, as the rejection is expressed not only by the well-off residents of upscale neighborhoods, but as well by those of working-class areas once they too become overcrowded.

I suggest the idea that overtourism lies at the intersection of two phenomena: the increase in short stays and the excessive media coverage of certain destinations in a world where communication rules prevail.

The multiplication of long weekends or short breaks, replacing the traditional long holidays, is a well-established trend, especially in post-industrialized Western European societies. The gradual decline in the cost of air travel, the increase in connections provided by low-cost airlines, along with changes in lifestyles and consumption habits, the emergence of urban tourism, all contribute to the phenomenon. The development of tourism among seniors, who are free from constraints related to school calendars due to the aging population in major emitting countries, plays a significant role in this trend.

Gone are the 19th-century days when the English gentry invented modern tourism with the Grand Tour, embarking for several months to discover Italy and the Mediterranean world (the word “tourism” itself comes from the expression Grand Tour). Has also vanished the more recent era when bourgeois families used to spend several weeks in summer by the sea.

Not all is bad in this evolution. The increase in the number of departures reduces their seasonality and the excessive dominance of summer vacations. However, this seemingly favorable trend is to some extent mitigated by the excessive focus placed on certain short stays. A glaring example of this new kind of imbalance is the concentration of Chinese holidays around three weeks of the year—the Chinese New Year, for which 9 billion trips have been registered in 2025, National Day, and the Mid-Autumn Festival. Another striking example is the importance that Americans give to the long Thanksgiving weekend. In Italy, the whole country is at the beach on August 15th—Ferragosto. The result is a congestion in the transportation systems, an increased pressure on the environment and the monuments, and the neglect of ecotourism. Ultimately, a less sustainable tourism.

You can’t do or see everything you would like in just a few days. Visitors going to Prague will limit themselves to this marvelous city, overlooking the rich cultural treasures of the nearby Bohemian countryside. Those heading to Madrid will likely ignore the medieval cities of Toledo and Segovia, the austere monastery of El Escorial, the delicate Aranjuez palace-garden, and the royal site of La Granja with its castle and park.

*******

This first phenomenon of the multiplication of trips, which have become both easier and shorter, intersects with another: the immediate and massive flow of information in a globalized society. Through the media, the internet, and social networks, tourist-consumers know what the world can offer. They zap through their screens, and they can easily make their choice among the places they would like to visit; but this all depends on how these destinations are presented, highlighted, and publicized.

After the first revolution which followed the emergence of e-tourism, a second one is rapidly coming with the earthquake resulting from the use of artificial intelligence. It will concern the tourism industry by many aspects, the first one being the leverage provided to the consumers in the way they plan, book, and live their travel experiences.

AI or not, many of the potential travelers wish to stay only briefly in the place they have selected. Enlarging their experience or boosting their understanding of the world are not their purpose. Just a souvenir, a post-card or a photo may be enough for them. As a consequence, as several other museums whether in totality or partially, the Prado in Madrid has forbidden to its 3,5 million visitors to take photos of its collections.

At the end of the day, the knowledge of the variety of the possible options and the constraint of a short stay collide. The travelers who want to travel often will limit their ambitions. Their choice will inevitably fall on the most well-known destinations and attractions, the ones enshrined in the media. As a result, they will overlook others.

International tourists often aim to maximize the number of countries they can discover in a single trip. First-time travelers from China may embark on a one-week group tour covering two or more European nations, but only experiencing a brief glimpse of each. They will discover Florence only through the Gucci megastore and the Michelangelo’s David statue (not realizing that the one in front of the Palazzo Vecchio is a copy) ; they will know London only through Harrods and Westminster Abbey (the latter seen from the exterior as they prioritized shopping) ; they will explore Paris only through the Galeries Lafayette and the Mona Lisa at the Louvre (which they didn’t really look at, too busy snapping selfies while other visitors are trying to capture her mysterious smile).

*******

Often, in their selection process, the ones deciding on their destination will base their choice on the presence of a cultural, natural, or mixed site listed on the prestigious World Heritage list, which was created by the 1972 UNESCO Convention.

If, by some extraordinary chance, a visitor from faraway Asia devotes an entire week to Italy, how can he or she possibly discover each of the 60 properties listed there? Similarly, like Marco Polo dazzled by the treasures of China in his Book of Wonders, the European tourist visiting the Middle Kingdom will struggle to make a selection between its 40 cultural sites, 16 natural sites, and four famous mountains offering both types of attractions.

For major museums, this phenomenon of “skimming” can occur internally: some visitors come only to contemplate a small number or even a single work of art in front of which they make their selfies. The selection of the “crème de la crème” includes the Mona Lisa at the Louvre (9 million visitors), the Creation of Adam in the Sistine Chapel within the Vatican Museums (7 million), the Rosetta Stone at the British Museum (6 million), or Guernica at the Reina Sofia Museum (3 million) …

The existence of sites recognized by UNESCO is a double-edged sword. Since it draws attention to the value of a property, the list encourages maintenance and preservation. Conversely, it leads to overcrowding, degrading the visitors experience and sometimes fostering the degradation of the site. At the same time, tourists will ignore other equally remarkable sites that were not selected on the List.

Things become more confused when the remarkable cultural attractions you are looking for have moved from one corner of the Planet to another. The most beautiful pieces of art of the Greco-Roman antiquity can be found in Rome and Athens, but also in London, Paris, or New York. The treasures of the imperial Beijing Forbidden City are kept in the National Palace Museum of Taipei. The most beautiful collections of the French impressionists’ paintings can be found in Paris, in the Orsay Museum, but also in Saint-Petersburg, London, New York, Washington and Chicago. Since 2017, the Parisian Le Louvre is also present in Abu Dhabi where it has received 1,2 million visitors in 2024. It should be rejoined in the coming months on the same island site by two other colossi, the Cheikh Zayed and the Guggenheim museums, the last one being already established in New York, Bilbao and Venice.

The fame that guides the choices of those about to depart can, in some cases, take strange turns. Chinese tourists, to admire the lavender fields, appreciate their fragrance and take photos, crowd into the lavender fields of the Valensole plateau in Provence, made famous by a well-known TV series in China. Even more surprising is the example of the Swiss village of Iseltwald, with its 400 residents, made popular by a South Korean Netflix series. To prevent the peaceful visitors from the land of the Morning Calm from staying too long, the local town hall has imposed a 5 Swiss francs tax for taking a selfie on a pier on Lake Brienz, where some romantic scenes were filmed.

Now we know where the gold resting in Swiss vaults comes from, but all of this is far from sustainable tourism.

The issue of sustainability in tourism is a huge undertaking for an industry that has become globalized. Let’s be more precise: with the often-overused word “sustainability” and the expression “sustainable tourism” plastered everywhere to the point of becoming a cliché, what exactly are we talking about?

It all started in 1987 with a report which produced intellectual consequences that no one had expected. But not just any report, the one commissioned by the United Nations, from a committee chaired by former Norwegian Prime Minister Gro Harlem Brundtland, entitled Our Common Future.

In the Brundtland report, we find the essential definition, the starting point for the journey that would follow: “Sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.”

This concept includes the idea that development must respect what John Elkington would later call “the three bottom lines,” the triple social, environmental, and economic responsibility—or the 3Ps: “people, planet, and profit.” With the notion of sustainability, the focus is placed on social justice and the fight against poverty. Equal attention is given to the environment, to the fight against pollution, and to the dual risks of climate change and loss of biodiversity. But the approach does not neglect, far from it, economic growth—the profit that businesses must generate and without which nothing is possible.

Sustainability must be pursued both globally and locally, one driving the other. This is the principle: “Think global, act local!”.

Let’s not make a mistake: sustainable development is primarily a principle… of development. Contrary to what some ecological extremists would make us believe, it is far from a strategy of decreasing or decay.

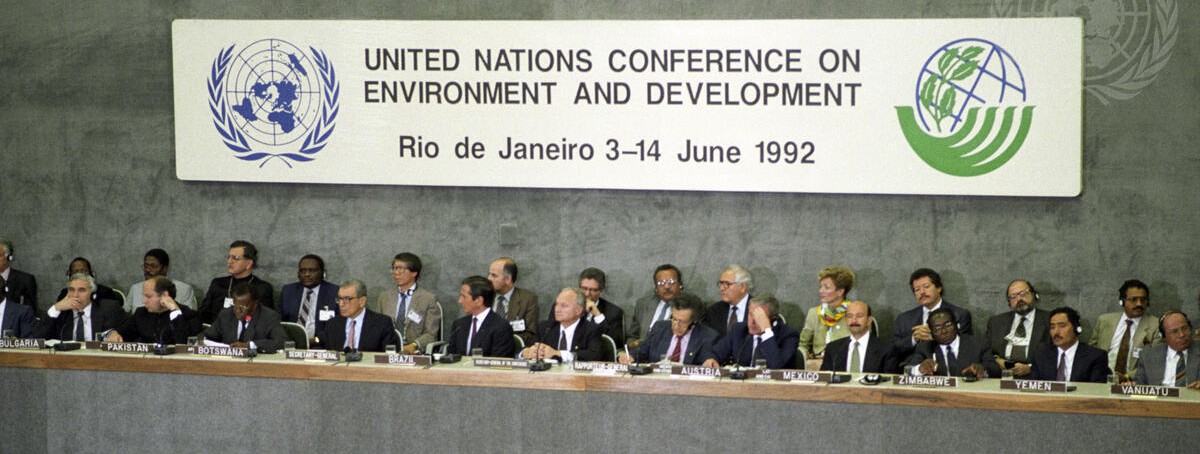

The Brundtland report became the intellectual foundation of the Earth Summit, the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, held in Rio de Janeiro in 1992. There, the Rio Declaration, Agenda 21, the Climate Framework Convention (which would later be extended by the Montreal and Kyoto Protocols), and the Convention on Biological Diversity, which introduced the “precautionary principle”, were adopted. A true festival!

The Summit gave rise to the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP).

In the wake of this extraordinary event, the Convention to Combat Desertification was adopted in 1994, applying the sustainable development concept to arid lands. A large portion of the territory of a major tourist country like Morocco is concerned.

The three phenomena—global warming, biodiversity loss, and the expansion of deserts and arid zones—interact in complex ways that go beyond the scope of this presentation. However, it is certain that climate change is the matrix of all of these. All three have a proven and generally negative impact on the tourism activity.

This is the case with biodiversity, whose existence is at the heart of many tourism products. In addition to climate change, it is threatened by accelerated deforestation, uncontrolled urbanization, intensive agriculture, overhunting and overfishing Various types of pollution, and the presence of invasive alien species can also contribute to it. The urgency is palpable: one million species, out of the 8 million (plants and animals) on the planet, are threatened by a possible extinction.

Let’s listen to Joan Baez and Marlene Dietrich singing Peter Seeger’s romantic ballad:

“Where have all the flowers gone?”

“Long time passing.”

“Where have all the flowers gone?”

“Long time ago.”

Still, we must not succumb to discouragement; there is no room for fatalism. The trend can often be mitigated, if not reversed. As General de Gaulle wrote in his Mémoires: “Suddenly, the song of a bird, the sun on the leaves, or the buds of a thicket remind me that life, since it appeared on Earth, has fought a battle it has never lost.”

*******

Everyone is aware that words in one language are sometimes difficult to translate into another, especially when the concepts they aim to express are not exactly the same. Such was the case with the original English expression “sustainable development”, used in the Brundtland report. For a time, there was hesitation in French between the terms développement durable (sustainable development) or développement soutenable. The latter was ultimately abandoned in French, and the former prevailed—perhaps because soutenable too closely resembled the word souteneur (“pimping”).

But the dual meaning underlying the English words sustain, sustainable, and sustainability remains: the idea of a necessary developmental effort to meet both current and future human needs, and the conviction that this effort only makes sense if it takes place in the long-term. Included in the concept of sustainability is the notion of resilience (another anglicism in French language, but what can we do?).

Sustainability is thought of in terms of development, which takes into account changes that may occur over time in economic and social structures, not just growth, which, in the short term, may neglect these changes. Sustainability focuses on future generations. The idea of immediate profit and speculation is foreign to it. It ignores Keynes’ sharp quip: “In the long run, we are all dead.”

*******

And where does tourism fit into all of this?

The truth is that, within the UN System, tourism hopped on the bandwagon of history in a search for a better world. It wasn’t until the turn of the 2000s that tourism became involved in the United Nations system’s commitment to develop in a sustainable manner this “Earth of Men” that Antoine de Saint-Exupéry speaks of.

In 1992, tourism was notably absent from the Rio Earth Summit. It was only after a lot of pushing that the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) and the World Travel & Tourism Council (WTTC) jointly published, a few months later, a document pompously titled Tourism in Agenda 21. This was almost a case of deception, as the Rio Conference had barely acknowledged the sector.

Consequently, tourism wasn’t included in the eight Millennium Development Goals adopted in 2000, which ran until 2015, with the first target being to halve the proportion of the global population living on less than a dollar a day between 1990 and 2015. A goal that was indeed met.

However, among world leaders—governments, the United Nations family of organizations, and Bretton Woods institutions—something was changing, as the growth of tourism flows was obvious and making its impact felt in countries where it had been least expected.

The UNWTO rode this wave. In 2002, it organized the first Global Ecotourism Summit in Quebec, in collaboration with the UNEP (United Nations Environment Programme). That same year, the UN held its new Summit in Johannesburg, ten years after the Rio summit (“Rio + 10”). It was a turning point. The UNWTO made sure tourism was included, especially for African countries, in the action plan which was adopted. Following this inflection, the Organization launched its STEP initiative—Sustainable Tourism for Eliminating Poverty. That episode in South Africa was a great moment of enthusiasm for me: a milestone -without a doubt, one of great significance- had been reached!

Let’s pause for a moment to focus on the emphasis placed at that time on ecotourism, as 2002 had been declared the “International Year of Ecotourism” by the United Nations. The concept was not as familiar then as it is today. Ecotourism is now defined as “a form of sustainable tourism focused on nature, where the main motivation is the visit to untouched or minimally disturbed natural areas, with the goal of admiring or studying the landscape, flora, fauna, or participating in traditional cultural events found in these areas.”

“The spectacle of nature is always beautiful”, wrote Aristotle. That was 21 centuries before the start of the industrial age. For the modern city-dweller, surrounded by congestion and pollution, ecotourism plays a role similar to H.G. Wells’ famous Time Machine—both a journey through time and a refuge in space.

Ecotourism is about visiting without damaging the integrity of the natural environment: “Take only photos, leave only footprints,” is the guiding principle. The conclusion of the Quebec Summit was clear: ecotourism is a form of sustainable tourism, the most demanding one, but the two concepts are not identical.

Ecotourism has characteristics that were identified during the Quebec Summit and have been accepted ever since. It includes a significant educational and interpretive component. The proper qualification of specialized guides and escorts is essential to its success.

Ecotourism is practiced, if I can put it this way, in an organized group, generally but not exclusively in small groups arranged by specialized tour operators. Service providers in destinations are often small local businesses.

The practice of ecotourism is a perfect illustration of the existence of a Keynesian multiplier in tourism activity, which, based on its cross-sectoral nature, establishes that the impact of an initial tourism expenditure is greater the fewer the “leaks” in the system, which is the case when the operators are local SMEs, and when visitor expenditures are directed towards services and goods (agricultural products, crafts) that come from the host community.

A stay at a rural guesthouse, a bed and breakfast, or a farm inn can generate, for a lower price point, greater positive economic and social returns for the community than a stay at a top-luxury hotel.

Ecotourism, like rural tourism, which is closely related, involves the consumption of local products and the minimization of resulting waste. Short circuits and the circular economy, as we strangely call it today.

“Sustainable tourism means traveling differently, more slowly…” writes sociologist Jean Viard. Sustainable tourism, ecotourism, nature and discovery tourism, rural tourism, village tourism, community-based tourism, or even slow tourism for the more pretentious, the concepts interlock with one another. All have in common the goal of making tourism more responsible and resilient. Resilient, meaning resistant. We’ve seen it: resistant to two brutal wars and a terrifying pandemic.

Ecotourism, I’ll come back to it, should only have limited negative impacts on the natural and sociocultural environment.

Here, let’s take the counterexample of the large cruise ships that now invade not only the coasts of Alaska and Norway but also the southern polar regions, some of them in violation of the 1959 Antarctic Treaty.

Their purpose is supposedly to observe the landscapes and terrestrial and marine wildlife. Yet, on the reality, they often harm the latter and contribute to the acceleration of climate change, which is already frighteningly present in these areas, to the point that the mythical Northwest Passage could soon be open to navigation, sparking interest from president Donald Trump to Canada and Greenland (in spite of climate change, Greenland is still basically white).

The Arctic snow and ice are melting, glaciers are fracturing, giving birth to new icebergs. The world described by Pierre Loti in Pêcheur d’Islande is gone. How sad! Can’t we let the penguins, seals, and bears fish in peace?

*******

As the UNWTO emphasizes, ecotourism promotes the protection of natural areas that support ecotourism activities, such as the national parks of East and Southern Africa.

It provides resources to those working to preserve these natural areas and contributes to job creation in nearby villages. In Rwanda, it costs $1,500 to have the privilege of meeting the impressive mountain gorillas in the Volcanoes National Park, but a quarter of the proceeds are donated to the surrounding local communities.

Whether it’s with the mighty elephants of Thailand or Sri Lanka, the sleek white dolphins of the Mekong in Kratié, Cambodia, or the exquisite giant pandas of China, whose survival has been preserved thanks to research centers like the one in Chengdu, Sichuan, the presence of ecotourism brings resources -especially fiscal ones- that allow endangered wildlife to be saved. Entry to the research center costs $20, while a visit to the Chengdu panda base is $70. It’s a reasonable price, especially since these clumsy big bears are so funny!

In Nara, Japan, the gentle deers, which are the city’s landmark attraction, are overfed by visitors; they proliferate and become greedy when it comes to the quality of the treats they are begging for. At Angkor Vat, which receives one million visitors, the local monkeys become aggressive. Finding the right balance between a high frequentation level that enriches and an excessive influx that disturbs and destroys is often difficult.

Let’s illustrate this with a particularly relevant example: the Galapagos Islands, 1,000 kilometers off the coast of Ecuador. By allowing 100,000 tourists each year, the Galapagos Islands put at risk a unique wildlife, including giant tortoises, land and marine iguanas, penguins, and albatrosses. Observing this fauna allowed Charles Darwin to formulate his famous theory of evolution in The Origin of Species. The archipelago is listed as a UNESCO World Heritage site and is one of the world’s biosphere reserves. In order to limit visitation and reduce the damage caused by excessive and poorly calibrated tourism, the Ecuadorian government recently raised the entry fee for foreign tourists to the national park from $100 to $200.

Moreover, by its presence, ecotourism acts as a game changer: it raises awareness among both local inhabitants and tourists about the necessity of preserving natural capital. When governments themselves are convinced of this, the best future becomes possible, as demonstrated by Costa Rica, which prefers forest rangers to soldiers, having abolished its army.

The recognition of tourism’s place within the international community came in the early days of 2004. Encouraged by Secretary-General Kofi Annan, it consisted of the transformation of the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) into a “specialized agency”— the expression meaning a full-fledged member of the United Nations System.

I take pride in having initiated this effort and in having driven it through to completion through a cooperation agreement -an international treaty- unanimously approved by both the UNWTO and the UN General Assemblies.

The next step, to which I also contributed, was the inclusion of tourism in the UN agenda on climate change at COP 13 in Bali in 2007. This was followed by the UNWTO’s active participation in the 2012 “Rio+20” World Summit and the appearance of tourism in three of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs—Goals 8, 12, and 14), which, starting in 2015, replaced the ancient Millennium Development Goals and will, we hope, guide the international community until 2030.

As indicated in General Assembly resolution 77/178, dated December 28th, 2022, the United Nations now considers that “sustainable tourism, including ecotourism, is an important driver of sustainable economic growth, social and cultural development, as well as the creation of decent jobs and entrepreneurship for all.” Provided that it is sustainable, tourism has the capacity to “eliminate poverty by improving the livelihoods of local populations.” By another concurrent resolution, February 17th has now become World Tourism Resilience Day. And the icing on the cake: by its resolution 78/260 of February 26, 2024, the same General Assembly declared 2027 the International Year of Sustainable and Resilient Tourism.

However, much remains to be done, especially for rural and village tourism. There was a time when the UNWTO, especially in East Asia and Africa, led local development projects funded by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) or the STEP Foundation. That time is over; unfortunately, communication has routinely replaced action and certification has replaced funding. In recent years, the UNWTO’s intervention has been mostly reduced to a kind of contest straight out of its “tricks and gimmicks” section, called “Best Tourism Villages”. At the end of 2024, the first international conference on Rural Tourism was held in Vietnam, but it’s too soon to know whether it will lead to any concrete follow-ups.

The most effective action now is led on behalf of the UNWTO and UNEP by the Global Sustainable Tourism Council (GSTC), an international NGO under U.S. law, established in 2008 in partnership between UNWTO, UNEP and another NGO, the Rainforest Alliance. The intention at the time was to increase the effectiveness of the action of the UNWTO, not to delegate it. The GSTC sets global sustainability standards for hotels and tour operators on the one end, destinations on the other. It does not conduct certifications by itself but accredits those mechanisms and bodies which do it.

Similarly, the Global Centre of Excellence for Destinations in Montreal, created in 2006 by the UNWTO with Canadian partners, certifies the quality of urban and rural destinations in about 70 countries.

In short, the UNWTO is doing its best to sow kids everywhere. Each of them sells its own version of the story, while the UNWTO, instead of looking after its turbulent offspring, behaves like the sluggish cow that watches trains passing by. The Organization is not playing “the decisive and central role in global tourism” that the United Nations recognized to it in 2004 with Article 1 of resolution 58/232 of its General Assembly.

*******

1992–2022: The endeavor lasted 30 years; the road was long, often winding, sometimes strewn with obstacles, but since the effort was not slackened, it led us to our goal.

To mark its completion, the UNWTO decided in 2024 to adopt the name “UN Tourism,” though it’s unclear what that move really means.

Either, indeed, a new official name has been given to the Institution, in which case it would be an act of malfeasance, because only an amendment to Article 1 of the Statutes, where this name appears, could have made it possible.

Or is it just a practical designation, but, in that case, what’s the added value of that since the existence of a direct reference to the United Nations already exist with the acronym “UNWTO”? Why paying a hefty sum for such a useless rebranding? And what’s the point of the absurd new logo which has been adopted?

Thank goodness that these days ridiculousness no longer kills!

*******

To conclude, let me briefly evoke the history of my country. In 1794, after the brilliant victory of Fleurus, the French Revolutionary soldiers first sang Le Chant du Départ. They proclaimed to Europe: “Liberty guides our steps.” For us who work for the future of the tourism industry, let sustainability guide our steps!

Let sustainability, the major of the various challenges that tourism today is facing, come before all other considerations of immediate profit, which breed inequities. “Never sacrifice the future for the present,” said French Prime Minister Pierre Mendès-France.

Let us fully commit ourselves to tireless genuinely pursuit sustainable and responsible development —a kind of development which is truly maintainable over time.

Let sustainability take precedence over the ease of unchecked growth driven by force, which leads to unbearable pollution, reckless use of land, and unsustainable consumption of natural resources.

Let us not accept the false shortcuts. Let us not settle for greenwashing or lip service!

Sustainable development is the new paradigm of the 21st century. It is both an imperative and an opportunity for tourism. It is a noble cause. It is a rewarding fighting.

Copyright Institute of Tourism